iStock

iStock

Tanisha uses an app to order tomatoes when she realises she's run out

Tanisha Singh is getting ready for work early one morning and cooking a simple curry for her lunchbox when she realises she's out of tomatoes.

Onions are already frying in the pan. Going out to buy vegetables is not an option, as local vegetable vendors won't be open.

So Tanisha picks up her phone. On a quick-delivery app, tomatoes are available.

Eight minutes later, the doorbell rings. The tomatoes have arrived.

What might feel remarkable in some parts of the world has become commonplace in Delhi and other big Indian cities. Groceries, books, soft drinks and even the occasional iPhone can now be delivered to people's doorsteps in minutes.

It's a convenience many don't strictly need, yet have quickly grown used to.

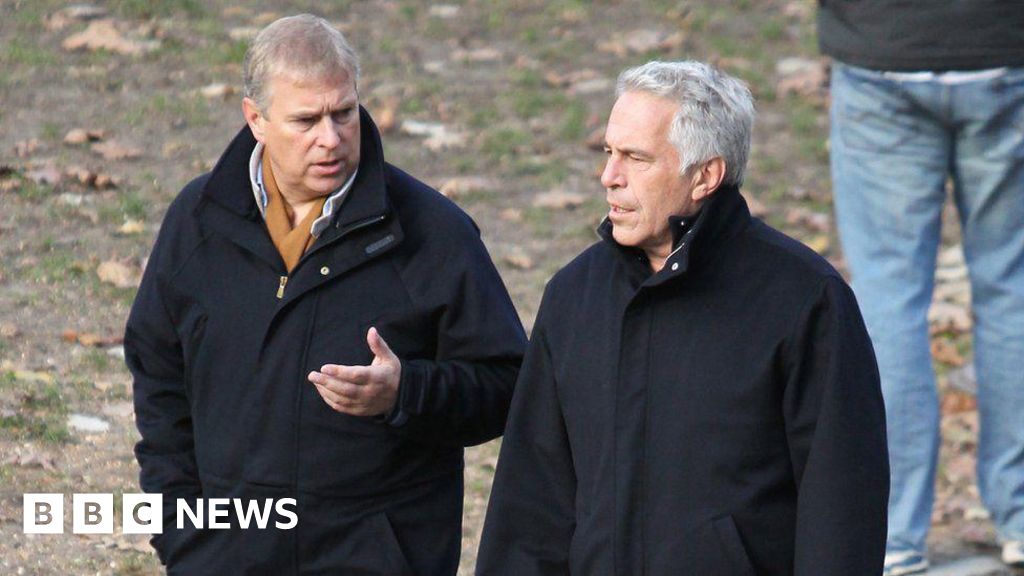

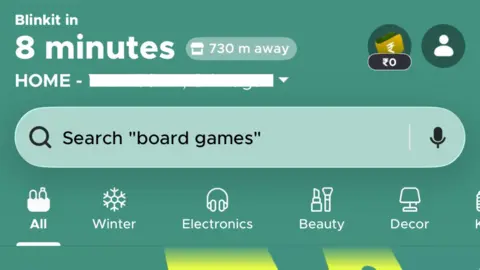

Unlike traditional retailers, platforms such as Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart and Zepto don't deliver from large supermarkets or distant warehouses. Instead, they operate out of small storage units embedded deep inside residential neighbourhoods.

Known as "dark stores", these facilities are typically located just a few kilometres from customers, allowing delivery riders to reach homes in minutes.

Think of them as a mini version of Costco - packed with essentials, but designed purely for speed. And because customers never walk into these spaces, everything inside is arranged for fast picking rather than browsing.

To see how this works, the BBC visited one such dark store in north-west Delhi.

Reuters

Reuters

Quick-commerce companies offer super-fast deliveries in India

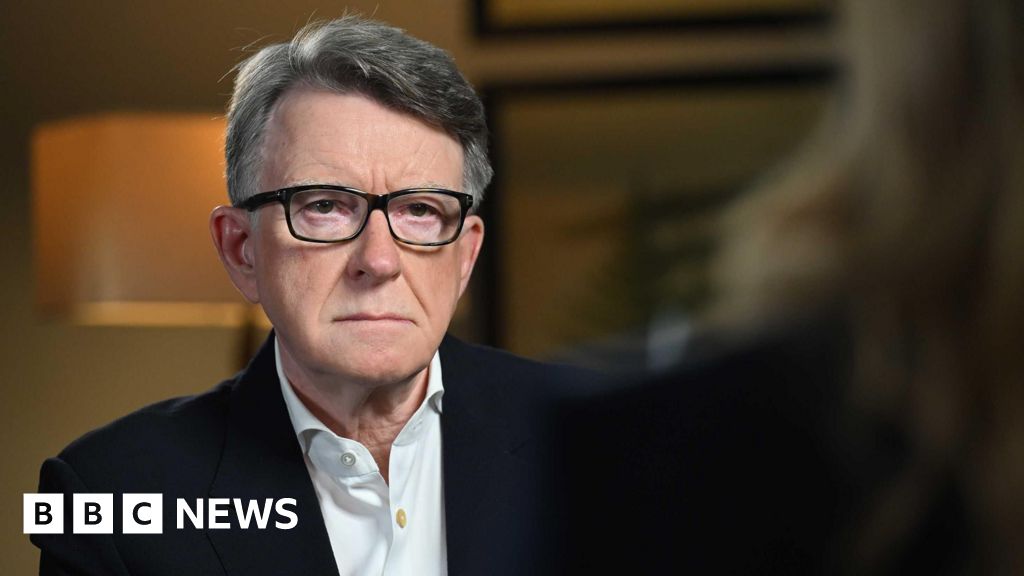

Inside, goods are stacked neatly on racks - with vegetables in one section, freezer units in another corner, and shelves stuffed with crisps, fizzy drinks and even pet food.

The aisles are so narrow only the workers can weave through them, moving fast and rarely bumping into each other.

The moment an order pops up on the screen, workers jump into action - picking, scanning, and packing items into the trademark brown paper bags with such speed it almost feels robotic.

"Done in under a minute," store manager Sagar says proudly.

Delivery riders walk up to the counter, almost in tune with the packers. Packing and pickup happen almost simultaneously - every step planned to reduce the time taken, even by seconds.

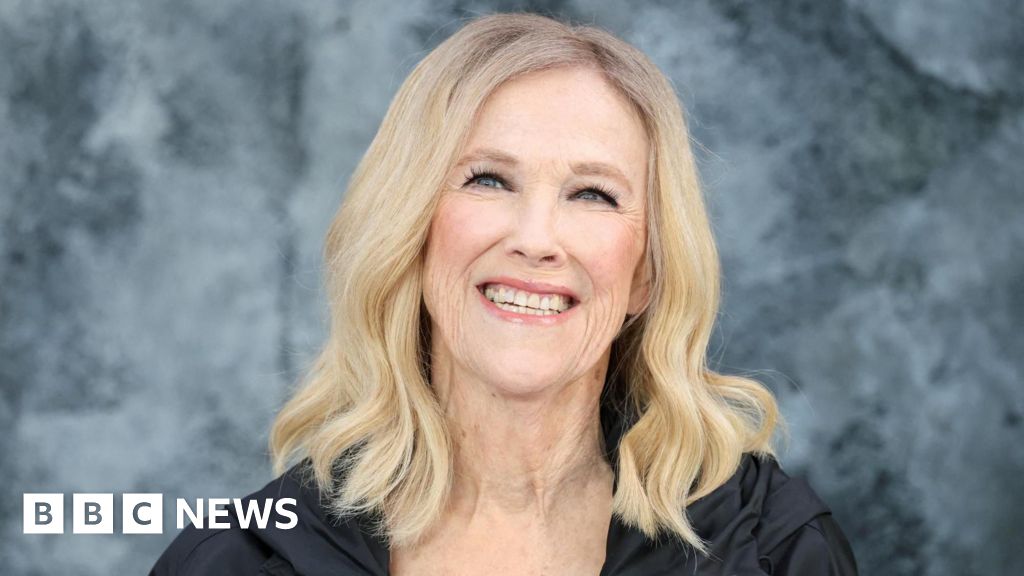

Delivery driver Muhammad Faiyaz Alam is 26. He collects a brown bag and agrees to let us join him for the ride.

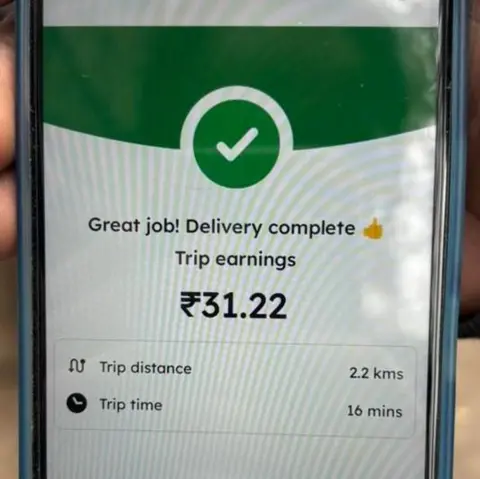

The destination is 2.2km (1.4 miles) away, about six minutes, according to the digital map.

There are no traffic lights on the route and he drives swiftly through narrow streets.

But the delivery doesn't end when we reach the location pin. In many dense Delhi neighbourhoods, lanes split unexpectedly, buildings look similar and proper addresses are often missing - things digital maps rarely catch.

People usually rely on landmarks instead - like "near the blue gate" or "behind the chemist" and so on.

Here, the drop‑off is "near a public bank ATM", which is not immediately visible.

Located just a short distance from customers, dark stores make ultra‑quick delivery possible in dense urban areas

So Alam calls the customer, follows their directions and eventually spots the right door.

From order to doorstep, the entire process takes 16 minutes. Alam earns 31 rupees (£0.25; $0.30).

He doesn't waste time after delivering the order and quickly heads back to the dark store, where another order is already waiting. The cycle repeats for hours, interrupted only by short food breaks.

The startlingly quick pace is closely tied to how riders are paid.

Alam says he tries to complete around 40 deliveries a day. On a good day, he takes home between 900 and 1,000 rupees, after deducting money spent on fuel and food. But his earnings fluctuate constantly, depending on order volume, distance, and the incentives offered by the app.

He is one of millions working in India's rapidly expanding gig economy, which is expected to employ 23.5 million people by 2030.

Low-paid convenience work is nothing new in India, but what has changed in recent years is the scale. Digital platforms have turned informal deliveries into a vast, app-driven workforce governed by algorithms.

Like most gig workers, Alam is classified as a "partner", not an employee.

He gets no fixed salary, no paid leave, and no social security. Although the government has promised labour reforms that could offer basic protections to gig workers, they are yet to be implemented.

NurPhoto via Getty Images

NurPhoto via Getty Images

Quick-commerce companies offer super-fast deliveries in India

Each day, Alam, like many other riders, logs in to the app and books his work slots, also called "gig slots".

The idea is simple - the more deliveries riders complete during those windows, the more "streak" incentives they unlock, boosting their pay and rewarding longer hours.

In December, Alam says he earned an additional 16,000 rupees through incentives alone. He completed more than 1,000 orders and worked 406 hours that month.

But this setup can unravel quickly for drivers.

Earlier this month, Alam's phone was stolen mid-shift. He had already worked five consecutive days for more than 12 hours and was just two days away from earning another 5,000-rupee incentive. Without his phone, he could not log in and his streak reset instantly.

"I was sad for a few days," Alam says. "But what can I do? At least I got the standard pay."

This incentive structure is not unique to India, but it is intensified by labour availability and weak worker protections, says researcher and author Vandana Vasudevan.

"These workers are classified as independent contractors, not salaried employees," she says. "They have no social security or benefits, yet algorithms still control their work through ratings, penalties and pay."

This pressure shows on the roads.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Goods are placed in these dark stores based on demand and accessibility

Alam admits he often speeds, squeezes through traffic and sometimes jumps signals to stay on target. Late deliveries can trigger customer complaints or warnings from managers.

Last month, delivery workers in several Indian cities went on strike over falling incomes, unpredictable incentives and unsafe conditions.

Experts say the move may not dramatically alter daily conditions for riders, but it does remove the expectation that every order should arrive within a fixed time.

To understand why that pressure exists at all, it helps to look at how quick commerce has grown in Indian cities.

The sector exploded after the pandemic, when lockdowns kept people indoors and crowded markets felt unsafe.

In many Western countries, grocery delivery services such as Getir surged during that period - but once the restrictions eased and people returned to supermarkets - many scaled back or were forced to shut down.

Muhammad Faiyaz Alam earned 31.22 rupees for a 2.2km ride

India, however, followed a different trajectory.

"In other countries platforms avoid committing to a fixed 10-minute promise and instead use terms like 'very fast' - thus lowering customer expectations. They also charge a premium for faster delivery, but in India there are no such constraints," she adds.

Here, you can even order a single avocado - and while it may cost a bit more than buying it from the neighbourhood shop, many urban consumers are willing to pay that premium simply to save time.

That willingness has driven its growth in metropolitan cities, says Ankur Bisen, a partner at retail advisory firm Technopak.

"Quick commerce has tapped into a huge pool of time-poor urban residents who spend long hours commuting and would rather order in essentials than step out again," he says.

Despite the buzz, quick commerce remains a small fraction of India's total retail economy and profitability remains elusive.

"They're still losing money," Bisen says, adding that these players are yet to come up with a sustainable business model.

Intense competition between Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, Zepto and now even Amazon keeps pushing companies to chase customers with ever-shorter delivery promises and heavy discounts in a price-sensitive market.

For users like Singh, quick commerce has shifted from an occasional convenience to a daily habit.

"It's not that I can't live without quick delivery," she says. "But I've grown so used to it that we forget it is a rare privilege and that there is human labour behind it."

There are signs that awareness is beginning to shift.

A recent survey by community platform LocalCircles found that 74% of respondents supported the government's decision to drop the "10-minute delivery" tagline. Nearly 40% said they were willing to wait longer for their groceries, rather than receive them at ultra-fast speed.

Whether that willingness translates into meaningful change on the ground remains uncertain. For now, the speed of India's cities is still being measured in minutes - and carried on the backs of workers who have little choice but to keep moving.

4 hours ago

3

4 hours ago

3