Gordon CoreraBBC Security analyst

BBC

BBC

It is a question that successive governments have struggled with: what kind of threat does China really pose to the UK?

Trying to answer it may have contributed to the high-profile collapse of the case in which two British men, Christopher Cash and Christopher Berry, were accused of spying for China and charged under the Official Secrets Act.

Both deny wrongdoing - but when charges were dropped last month, it sparked political outcry.

Prosecutors and officials have since offered conflicting accounts about whether a failure or unwillingness to label China as an active threat to national security led to the withdrawal of the charges. And yesterday Lord Hermer, the attorney general, blamed "out of date" legislation for the case's collapse.

But this all raises the question of what exactly Chinese espionage looks like in the modern world.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

What lies at the heart of the problem is that the national security threats China poses today go beyond traditional notions of espionage

On one level, China spies within the traditional framework of the old ways of human espionage associated with the Cold War, with spies working under the cover of being diplomats, and recruiting people to pass secrets.

The witness statement by a deputy national security adviser for prosecutors investigating the now-collapsed case of Cash and Berry outlines this kind of work.

"The Chinese Intelligence Services are interested in acquiring information from a number of sources, including policymakers, government staff and democratic institutions and are able to act opportunistically to gather all information they can."

Here is the thing though. Pretty much every country does this kind of spying - wanting insight into what other countries are up to is as old as the hills. The UK conducts this kind of espionage against China (as China itself has publicly complained about). When countries get caught there is normally a public row but each side knows it is normal business.

But this barely covers the breadth of the Chinese behaviour that worries security officials.

"Try not to think too much just in terms of classic card-carrying spies based out of the embassy in the John le Carre mould," the head of MI5 Sir Ken McCallum said during a briefing on national security threats earlier this month.

For what truly sets China apart - and what lies at the heart of the problem - is that the national security threats China poses go beyond traditional notions of espionage.

To complicate matters further, some of the threats are also closely tied up with the reasons many believe we need to engage with China.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Chancellor Rachel Reeves has said 'choosing not to engage with China is no choice at all'

China's economic power, for example, presents many potential benefits for a UK desperate for growth.

Labour is reported to be seeking to improve ties with China. However, securing the benefits of a relationship while navigating the associated risks is the hard task that has bedevilled governments.

Growing concerns about political influence

The sheer size of Chinese intelligence – which some estimates put at half a million when you account for the entire workforce operating on security both at home and abroad – means they can afford to pursue their work at a larger scale than many other countries.

Every country uses its intelligence services differently - how it does so throws a spotlight on the priorities of the state - and in China, the top priority is ensuring the continued rule of the Communist Party.

In practice this has meant influencing political debate abroad, going after dissidents, collecting data at a large scale and ensuring economic growth at home.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Every country uses its intelligence services differently - in China, the top priority is ensuring the continued rule of the Communist Party

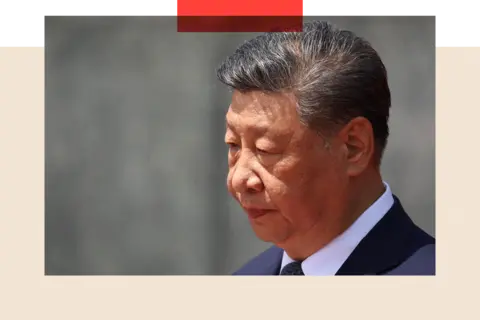

In the UK, concerns about Chinese political influence have been growing.

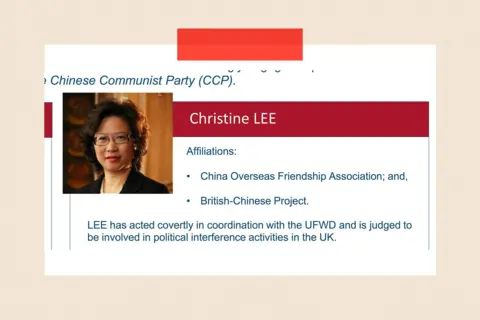

MI5 issued an "interference alert" in January 2022 about the activities of an alleged Chinese agent, Christine Lee, who was believed to have infiltrated Parliament.

Ms Lee denied the allegations. She later took unsuccessful legal action against MI5, and told a tribunal that the spy agency's alert about her carried a "political purpose".

MI5 has also warned that Beijing was cultivating local politicians in the early stages of their career with the hope of seeding them into more senior positions - a sign of a long-term, patient strategy to build influence.

PA

PA

MI5 issued an alert about Christine Lee, an alleged Chinese agent

Here, the purpose was not stealing secrets or gaining information so much as manipulating political debate – having people in influential positions who will take a pro-China view of issues and the world.

Another area that worries UK security officials is China's predilection for spying on dissidents, known as transnational repression, something that has been a primary target for Chinese intelligence for years with a focus on groups like Tibetan campaigners.

But the arrival in the UK of many young pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong, following Beijing's clampdown, has heightened the concerns.

According to MI5, Hong Kong police have issued bounties against more than a dozen pro-democracy activists here in the UK and there have been increased reports of harassment and surveillance.

Beijing has always dismissed accusations of espionage as attempts to "smear" China.

"China never interferes in other countries' internal affairs and always acts in an open and aboveboard manner," the Chinese embassy in London has previously said.

In a statement issued earlier this month, it added: "The so-called 'China spy-case' hyped up by the UK is entirely fabricated and self-staged. China strongly condemns this...

"China's development is an opportunity for the world, not a threat to any country. We firmly oppose attempts to smear China by peddling unfounded allegations of 'spying activities, or concocting the so-called 'China threat'."

Sophisticated cyber-espionage

Yet China has been linked to some large scale cyber operations. Some of this sits within modern notions of espionage – stealing secrets.

Last year Beijing was accused of trying to hack into the emails of MPs.

"China represents an economic threat to our security and an epoch-defining challenge," Rishi Sunak, the then-prime minister, said at the time, while avoiding formally labelling Beijing as a "threat".

Then, in August, the UK finally revealed what many suspected – that it had been hit as part of a highly sophisticated espionage campaign codenamed Salt Typhoon, which compromised telecoms companies around the world.

The UK remained quiet about who exactly was hit and only spoke out in conjunction with a dozen other countries and after months of discussion behind the scenes about what it should say.

PA

PA

Sir Ken McCallum: 'Try not to think too much just in terms of classic card-carrying spies based out of the embassy in the John le Carre mould'

"The data stolen through this activity can ultimately provide the Chinese intelligence services the capability to identify and track targets' communications and movements worldwide," the UK's National Cyber Security Centre, an arm of GCHQ, warned in a statement.

The US had spoken out months earlier, and there it has been reported that senior politicians, including Donald Trump and JD Vance, had their communications targeted during the 2024 election.

An 'alarming' appetite for data

Now, in the UK, plans for a new Chinese Embassy at the former Royal Mint building in London have drawn attention for fears that it could offer the chance for espionage by tapping data cables which run underground beneath it.

But some security officials downplay those dangers - not only because those cables can be physically protected and monitored - but because of Beijing's capacity for large cyber-espionage.

The reality is that it has shown itself perfectly capable of collecting data through remote cyber-access.

Plans for a new Chinese embassy at the Royal Mint in London have prompted protests

That kind of targeting, though, still sits broadly within traditional state-on-state espionage and the kind of thing Western governments carry out.

In fact it was the revelations about the scale of UK and US digital eavesdropping by former contractor Edward Snowden that may have spurred China to become more ambitious in cyber-space.

But in cyber-space, the real concern is broader.

What is notable about Chinese intelligence activity online is an appetite for data on a massive scale. Beijing's pursuit of what is often called bulk data - large scale data sets which might contain financial, personal, health or other types of information - is what alarms Western security officials.

"China has been trying to collect population level data on British people," according to Ciaran Martin, a former head of the UK's National Cyber Security Centre.

Getty

Getty

Revelations by Edward Snowden may well have spurred China to become more ambitious in cyber-space

"That may be useful to train artificial intelligence or to better understand the country or even influence opinion or possibly even to work out what our vulnerabilities are individually and collectively.

"It is not always effectively carried out but it is very different from the kind of 'normal' spying on government and politics that virtually all countries undertake.

"In this other respect, China is notable only for how brazen its spying sometimes is."

Some of this data is stolen but sometimes it is suspected to be acquired through Chinese companies with access to the Western market.

The stream of attempts to 'lure academics'

There is one element that is trickiest for national security officials to deal with when it comes to China: how to balance the risks and the benefits of China's growing economic power.

A priority for the Chinese state - and its spies - is ensuring economic growth.

Observers often point to a kind of unspoken bargain: the Chinese public will tolerate the relative lack of political freedom and continued one-party rule as long as the state delivers economic benefits.

That is one reason that China has also been active for decades in pursuing economic as well as political and diplomatic secrets in a way Western countries have not.

Sometimes this has been business secrets of companies – whether designs for new products or negotiating positions.

There are types of sensitive information that are not state secrets, like high-tech research into a new advanced material at a university, which has military as well as civilian applications.

MI5 says it is tackling "a steady stream of attempts to lure UK academic experts" in order to get hold of technology they are working on, often starting with approaches over networking sites like LinkedIn.

Getty

Getty

China has been active for decades in pursuing economic as well as political and diplomatic secrets in a way Western countries have not

"In a world where the 'DNA' of military and economic power is built on ones-and-zeros [of digital information], when core intellectual property and process knowledge leak, entire industries can be upended - and with them move jobs, capital, and geopolitical leverage," says Andrew Badger, a former US intelligence official and co-author of an upcoming book, The Great Heist: China's Epic Campaign to Steal America's Secrets.

"The UK's current debate about how to prosecute spies, strengthen laws, and balance commerce with security should start from this historical truth: economic power can only be sustained with the resolute custody of secrets."

The hardest risk to measure

As China's economic power grows – especially in advanced technology – one of the hardest risks to measure is the UK and other Western states' dependence on China in critical fields, including electric vehicles and critical minerals used in manufacturing.

This underpinned the debate about the Chinese telecoms company Huawei building a large part of the country's new 5G phone infrastructure.

Chinese equipment was cheaper and often seen as better than those of competitors - but were there risks?

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Chinese telecom giant Huawei at a display for journalists in Shenzhen

It was less about using it to spy - and more the fact that a relationship of dependency on another country for technology on which daily life depends opens the way to influence and even coercion. If you do something or say something Beijing does not like, could it cut you off?

In the end, technology from Huawei - which always denied it was a security risk - was excluded from 5G. But it was only the first Chinese company to go global and now there are many more.

So, does it matter if China builds new nuclear reactors? Or becomes the main supplier of green technology? And what about if people depend on the Chinese-originated social media platform TikTok for their news and information?

This is the area where the tension with the economic growth agenda become clearest. China is the second largest economy in the world, an important export market and source of investment. If we want to secure the benefits of this relationship then it becomes much harder to exclude Chinese companies from the UK market.

Any kind of blanket ban on Chinese technology or companies would be absurd. But just how much should we open ourselves?

Getty

Getty

John le Carre's novels - including The Spy who Came in From the Cold - shaped how we think about spying. But in this new world, threats are more complex

The other challenge for Britain is that, in many of these areas where economic and national security mix, the US is taking a tougher stance - and Washington is seeking to pressure London to come into line.

That leaves London caught between pressure from Beijing and Washington and trying to work out how to address these threats while also maintaining productive relationships.

None of this is easy - and not much of it is to do with traditional spying. In this new world, threats are far broader and more complex.

But without a clear, consistent China strategy that is confidently expressed, this government – like previous governments - will continue to find it hard to know how to navigate.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.

3 months ago

84

3 months ago

84