Orla Guerin in northeastern Syria

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

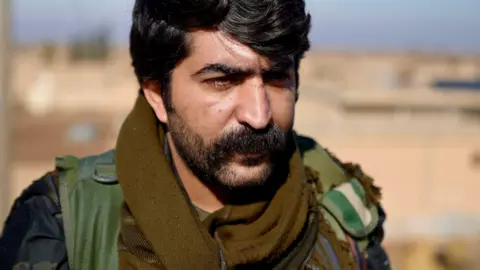

Commander Azad feels betrayed by his former US allies

As a veteran Syrian Kurdish fighter, Commander Azad – whose nom-de-guerre means freedom - walks with a limp and wears his battle scars with pride.

"My leg was injured when we were bombed by a Turkish warplane in 2018," he says. "And this was shrapnel from a suicide bomber," he adds, rolling up his sleeve to reveal a deep gouge in his arm. "My back, abdomen and lower body were all injured in four separate attacks by Daesh," he says, using the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State group (IS).

His latest wound is below the surface, and cuts deep – what he sees as betrayal by a former friend, the United States. After IS seized around a third of Syria and Iraq in 2014, the US and the Kurds worked hand in glove to drive them out.

"History will hold them accountable," says the commander, who has a handle-bar moustache and wears a green fringed scarf around his neck. "Morally it's not right. But we will keep fighting until our last breath. We are not cry-babies."

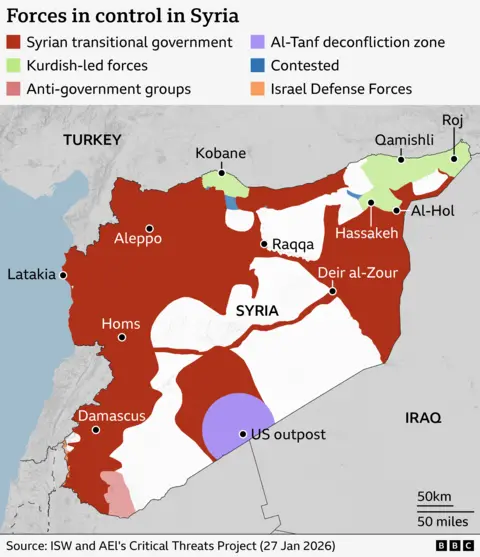

Their current fight is with the central government in Damascus which wants to extend its control across all of Syria, including the Kurdish autonomous region in the north-east.

In the past two weeks government troops have pushed the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) out of resource-rich areas they have controlled for a decade – since defeating IS.

As conflict has flared, the White House has strongly backed Syria's interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa - a former Jihadi. That's a slap in the face for the Kurds. The SDF lost 11,000 fighters battling the jihadis of IS.

Commander Azad compares the president to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the late founder of IS. "They are the same thing. After Jolani took over, Syria will always be a war zone," he says, referring to the president by his fighting name, Abu Mohammed Al Jolani.

Having fought US troops in Iraq, Al Sharaa set up an al-Qaeda offshoot in Syria, which was in fact fiercely opposed to IS though the groups had similar roots. He later broke with al-Qaeda, then in December 2024 swept to power in Damascus, ousting Bashar al Assad.

In the eyes of the Kurds, Al Sharaa is still a Jihadi, but now in a suit.

Commander Azad stiffly climbs the stairs to an open rooftop with a commanding view of flat countryside.

Below us sheep graze in the fields and clothes flaps on a washing line in a back garden. But a pick-up truck with an anti-aircraft machine gun is parked outside the door, and there is a cluster of troops in camouflage uniforms. This is the SDF's last checkpoint in their stronghold of Hassakeh province.

"They [Syrian government forces] are in an Arab village seven kilometres from here," he says, gesturing to the horizon. "So far, there is no danger. I hope there will be no war, but if it comes, 'Let it be welcome,'" he says, quoting Che Guevara, Cuba's revolutionary hero.

A fragile ceasefire between the two sides is due to expire on 7 February, but talks are continuing.

"We are focusing all our efforts on reaching a permanent ceasefire or a lengthy one," says Siyamend Ali, of the People's Protection Units (YPG), a Kurdish militia that is the backbone of the SDF.

"We don't want war, but if we are forced down that path we will fight back. Every neighbourhood will turn into a hell for them."

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Despite the sense of betrayal, the Kurdish forces remain defiant

Ali has already seen too many losses in the fight against IS. His fallen friends number in the hundreds.

"There were friends I studied with in school and university, and friends I played with. They were from my family and from neighbouring families," says Ali, in a low and weary voice. "They rose to martyrdom. Now I walk in their footsteps."

We met at another frontline position - where mounds of dark soil formed fresh defences. If all-out war comes, it will be a losing battle for the Kurds. But there are implications far beyond this corner of Syria.

Since the defeat of IS in Syria in 2019, this area has been a holding ground for the remnants of the group's so-called "caliphate". Kurdish-run prisons hold about 8,000 suspected IS fighters, and around 34,000 of their wives and families are detained in camps. Will the gates remain locked if this region becomes a battleground?

The Syrian government has taken control of one camp, al-Hol, in eastern Hassakeh.

When we visited last October - with an armed escort - we got a hostile reception from veiled women, clad head to toe in black. One ran a finger across her neck, as if slitting a throat.

The other main camp, called Roj remains in Kurdish hands. It's home to more than 2,000 foreign women and children, who have been convicted of nothing.

Rows of blue and white tents offer little protection from biting winter cold. Children play on a carpet of mud, ringed by fences, walls and watch towers. Roj is a prison in all but name.

'My children and I are paying the price' - The BBC's Orla Guerin spoke to two of the thousands of women who remain in Roj camp

We returned there this week to find the camp manager Hekmiya Ibrahim increasingly worried. She is slight but determined, a powerhouse in a headscarf. The detainees have been emboldened by the changes beyond the wire, she says.

"When news reached them [of the government take-over of al-Hol] everyone immediately came out of their tents, chanting 'Allahu Akbar' [God is greatest]. The sound of their chanting echoed throughout the camp."

Taking her phone from her pocket she shows me pictures of the black and white IS flag, newly daubed on one of the walls of the camp. And she recounts threats made to staff. "Statements were directed at us such as 'We will return', 'You are infidels', and 'ISIS will end you,'" she tells us.

She warns that some in the camp – even the young – pose a threat to the world.

"There was an incident last October involving twin brothers from Turkmenistan," she says. "One killed the other and later said he would do it again if his brother came back to life."

The reason – the slain brother was not radical enough.

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Goktay Koraltan/BBC

Hekmiya Ibrahim fears the detainees remain radical

But in the camp's cheerless food market we met women who pointed out that their children are guilty of nothing and pleaded for them to have a normal life. We spoke to two women from North Africa, who did not want to be identified.

"I want to leave this place," one woman said, "so my daughter can study and live her life. She has the right to an education, to visit a park, to get medical care. If she's ill, God forbid, she should be able to go to hospital like any other child, without soldiers going with us."

When challenged about the fact that they themselves came to join IS, her friend jumped in. "Firstly, I didn't join the organisation," she said. "My husband forced me to come here. He died, and my children and I are paying the price. Our children think the entire world is a camp behind a fence."

Forty Britons remain trapped behind that fence – 25 children among them. We came across one of them – a polite boy speaking good English who we cannot identify. He shook hands with one of my BBC's colleagues, and asked, "How are you?"

One woman from the UK told us she wanted to go home but was afraid to be interviewed as camp guards were hovering. Two other British women refused to speak, including Shamima Begum, who left London as a schoolgirl to join IS. Camp staff told us Begum was "hiding in her tent".

Recalling her decision to come to IS territory, a Bosnian woman broke down and wept. "I feel so bad because I came here with my husband, and I destroyed my life," she said. "I can't explain myself how I was stupid enough to come here. It was a mistake."

She says her husband was not radical when they met in college but changed over time. By then they already had a child. Her second child was born in Syria.

"We are really worried because we hear stories that there might be a war," she told us. "We really hope they will fix this issue peacefully and that finally we can go back to our countries."

As the sands shift in Syria countries that have been willing to leave their citizens in Kurdish camps indefinitely may have to think again – the UK included.

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3