Zoya Mateen

BBC News, Delhi

Auqib Javeed

Srinagar, Kashmir

UGC

UGC

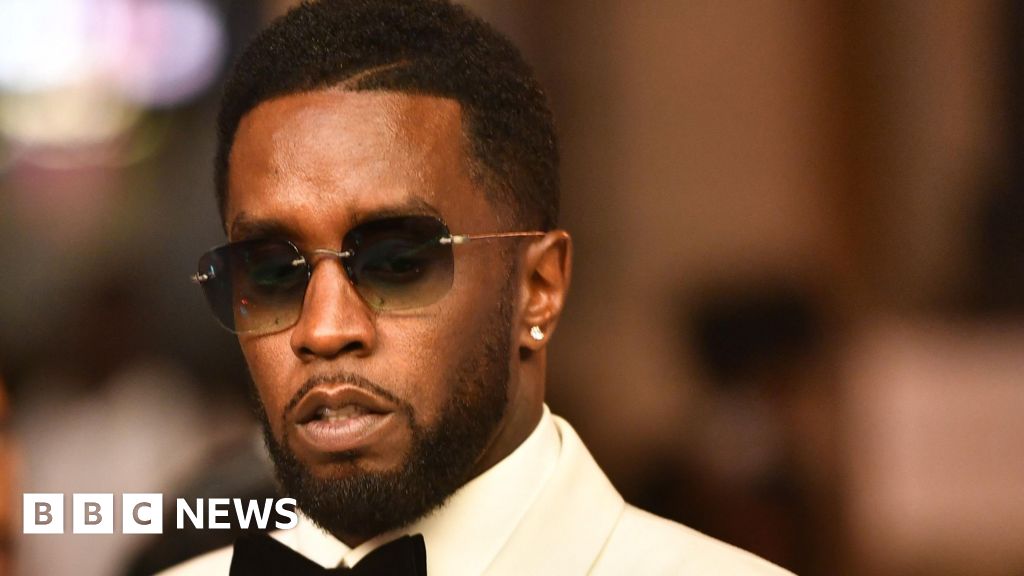

Two shawl sellers were assaulted in Mussoorie because of their Kashmiri identity

Shabir Ahmad Dar, a resident of Indian-administered Kashmir, has been selling pashmina shawls for more than 20 years.

The intricately embroidered featherweight scarves are a favourite with his customers in Mussoorie, a hill town in the northern state of Uttarakhand, where he works.

For his buyers, the shawls are a sign of luxury. For Dar, they are a metaphor for home; its traditional patterns layered with history and a mark of his Kashmiri identity.

But lately, the same identity feels like a curse.

On Sunday, Dar, along with another salesman, was publicly harassed and assaulted by members of a Hindu right-wing group, who were reportedly incensed by the killing of 26 people at a popular tourist spot in Kashmir last week. India has blamed Pakistan for the attack - a charge Islamabad denies.

A video of the assault shows the men thrashing and hurling abuses at Dar and his friend as they ransack their stall, located on a busy boulevard.

"They blamed us for the attack, told us to leave town and never show our faces again," said Dar.

He says his goods, worth thousands of dollars, are still lying there. "But we are too scared to go back."

As outrage over the assault spread, police on Wednesday arrested the three men but released them a few hours later after charging a fine and asking them to "apologise" to Dar and his colleague.

But Dar had already left by then, along with dozens of other Kashmiri shawl sellers, who, after living in Mussoorie for decades, say they no longer feel safe there.

Reuters

Reuters

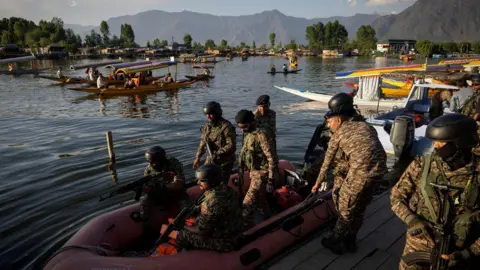

Additional security forces have been deployed in Indian-administered Kashmir since the killings

Many survivors of the Pahalgam attack - the deadliest targeting civilians in recent years - said the militants specifically targeted Hindu men, sparking an outpouring of anger and grief in India, with politicians across party lines demanding strict action.

Since then, there have been more than a dozen reports of Kashmiri vendors and students in Indian cities facing harassment, vilification and threats from right-wing groups - but also from their own classmates, customers and neighbours. Videos showing students being chased out of campus and beaten up on the streets have been cascading online.

On Thursday, one of the survivors, whose naval officer husband was killed in the militant attack, appealed to people to not go after Muslims and Kashmiris. "We want peace and only peace," she said.

But safety concerns have forced many Kashmiris like Dar to return home.

Ummat Shabir, a nursing student at a university in Punjab state, said some women in her neighbourhood accused her of being a "terrorist who should be thrown out" last week.

"The same day, my classmate was forced out of a taxi by her driver after he found out she was a Kashmiri," she said. "It took us three days to travel back to Kashmir but we had no option. We had to go."

Ms Shabir is back in her hometown but for many others, even home does not feel safe anymore.

As the search for the perpetrators of last week's attack continues, security forces in Kashmir have detained thousands of people, shut off more than 50 tourist destinations, sent in additional army and paramilitary troops, and blown up several homes belonging to families of suspected militants who they accuse of having "terrorist affiliations".

The crackdown has sparked fear and unease among civilians, many of whom have called the actions a form of "collective punishment" against them.

Without mentioning the demolitions, Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah said the guilty must be punished without mercy, "but don't let innocent people become collateral damage". Former chief minister Mehbooba Mufti also criticised the demolitions, cautioning the government to distinguish between "terrorists and civilians".

"Whenever tensions escalate, we are the first ones to bear the brunt of it. But we are still treated as suspects and expected to put our lives on hold," another student, who wanted to remain anonymous, told the BBC.

Reuters

Reuters

The attack in Pahalgam was the deadliest on civilians in decades

Yet the backlash feels a lot worse this time, says Shafi Subhan, a shawl seller from the region's Kupwara district, who also worked in Mussoorie.

In his 20 years of doing business there, Subhan said he had never faced any public threat - not even after the 2019 terror attack in Pulwama district, which killed 40 paramilitary police troopers.

To him, Mussoorie felt like home, a place where he found peace - despite being hundreds of kilometres away. He said he shared an emotional bond with his customers, who came from all parts of the country

"People were always kind to us, they wore our garments with so much joy," Subhan recalled. "But on that day when our colleagues were attacked, no one came to help. The public just stood and watched. It hurt them physically - but emotionally, a lot more."

Back home in Kashmir, peace has long been fragile. Both India and Pakistan claim the territory in full but administer separate parts, and an armed insurgency has simmered in the Indian-administered region for more than three decades, claiming thousands of lives.

Caught in between, are civilians who say they feel stuck in an endless limbo that feels especially suffocating, whenever ties between India and Pakistan come under strain.

Many allege that in the past, military confrontations between the nations have been followed by waves of harassment and violence against Kashmiris, along with a significant security and communication clampdown in the region.

EPA

EPA

Several homes allegedly belonging to suspected militants have been razed down

In recent years, violence has declined, and officials point to improved infrastructure, tourism, and investment as signs of greater stability, particularly since 2019, when the region's special constitutional status was revoked under Article 370.

But arrests and security operations continue, and critics argue that calm has come at the cost of civil liberties and political freedoms.

"The needle of suspicion is always on locals, even as militancy has declined in the last one-and-a-half decades," says Anuradha Bhasin, the managing editor of the Kashmir Times newspapers. "They always have to prove their innocence."

As the news of the killings spread last week, Kashmiris poured onto the streets, holding candlelight vigils and protest marches. A complete shutdown was observed a day after the attack and newspapers printed black front pages. Omar Abdullah publicly apologised, saying he had "failed his guests".

Ms Bhasin says Kashmiri backlash against such attacks is not new; there has been similar condemnation in the past as well, although at a smaller scale. "No one there condones civilian killings - they know the pain of losing loved ones too well."

But she adds that it's unfair to place the burden of proving innocence on Kashmiris, when they have themselves become targets of hate and violence. "This would just instil more fear and further alienate people, many of whom already feel isolated from the rest of the country."

Reuters

Reuters

Kashmiris have held widespread protests against the militant attack

Mirza Waheed, a Kashmiri novelist, believes Kashmiris are "particularly vulnerable as they are seen through a different lens", being part of India's Muslim population.

"The saddest part is many of them will suffer the indignity and humiliation, lay low for some time, and wait for this to tide over because they have a life to live."

No one knows this better Mohammad Shafi Dar, a daily wage worker in Kashmir's Shopian, whose house was blown up by security forces last week.

Five days on, he is still picking the up the pieces.

"We lost everything," said Dar, who is now living under the open sky with his wife, three daughters and son. "We don't even have utensils to cook food."

He says his family has no idea where their other 20-year-old son is, whether he joined militancy, or is even dead or alive. His parents say the 19-year-old college student left home last October and never returned. They haven't spoken since.

"Yet, we have been punished for his alleged crimes. Why?"

12 hours ago

9

12 hours ago

9